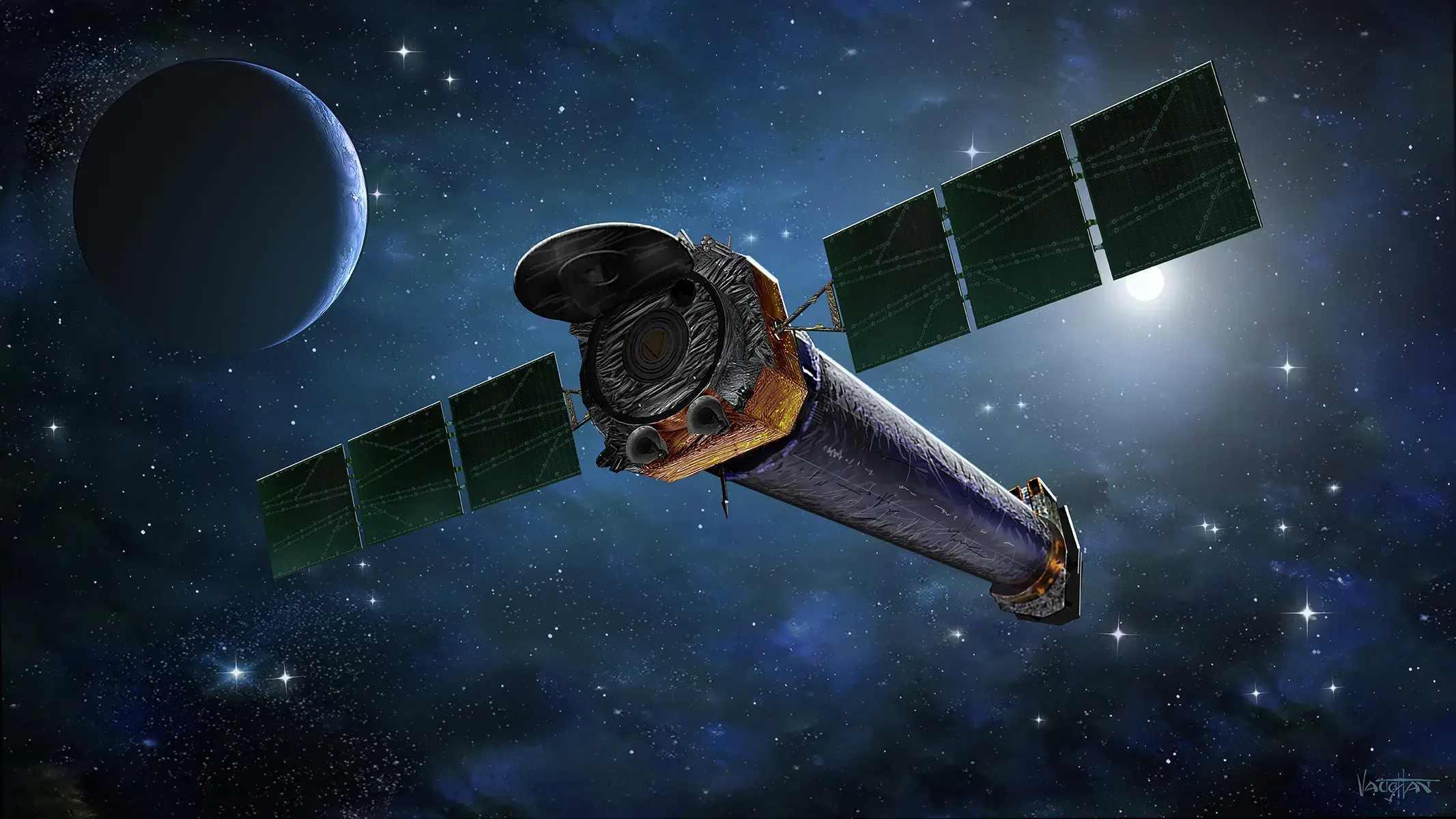

This is a commemoration piece for the announced decommissioning of the Chandra Space Observatory. May it always fly high, soaring amidst the X-Rays.

A massive star close to us has collapsed! Quickly, turn the telescopes (except for Webb, its sensors are too sensitive), start the sensors, and tell Chandra to scan for pulsars!

Wait. What?

Launched with the Hubble and Compton telescopes, the Chandra telescope was humanity’s first space-based X-ray observatory. Ground-based x-ray observatories, their sensors scrambled by the scattering effects of our atmosphere, are functionally useless - so for the roughly 3 centuries between Galileo’s model telescope and the launch of Chandra, the human race was functionally ‘in the x-ray dark’.

If you’re lucky, you might catch Chandra staring straight into a dark nebula. X-rays have the quirk of being able to avoid this scattering effect in these diffuse nebulae, allowing Chandra to view the clouds as if they were not there.

Pulsars are very dense, very hot objects that form from the cataclysmic collapse of a massive star. It’s outer layers fall onto its core at nearly 25% the speed of light - overcoming even the electrostatic repulsion of electrons to form a ball of pure neutrons. Their emissions - primarily in the x-rays due to their heat (and the black-body spectrum) reflect off the expanding cloud of dust and gas, creating a pulsar wind nebula. These beautiful structures are not unlike the planetary and H II regions we see that dot our night skies, just that they’re invisible to the naked eye - a job perfect for Chandra to resolve. Breathtaking images, the colours of which have been edited to better compensate for our own visible range, allowed for scientists and the public to peruse the structures for the first time - some of which were unlike any seen before.

Aside from the investigations through the dark clouds, the telescope has proven immensely useful in cataloguing the behaviours of other objects - brown dwarves, failed stars not massive enough to induce nuclear fusion in their cores, have been observed to emit X-Ray flares by Chandra. In addition, the telescope was the first to map out the structure of the supernova, providing us with never-before-seen

These discoveries make Chandra a true jewel, the lump sum of human ingenuity and wanderlust orbiting nearly 60,000 kilometers from the surface of the Earth. NASA, on the other hand, has decided that it’s still got to go. Chandra’s yearly funding is going down to a paltry $26.2 million - pocket change in telescope terms. It’s probable that there’ll be layoffs - and astronomers are livid at the fact that NASA’s gone ahead with this plan. By this point, Chandra’s more than quadrupled its expected operational lifetime - and the longevity of the telescope has resonated with many in the public, myself included.

The next X-Ray telescope isn’t due until the 2030s. There’s no telling when Chandra will take its last image, but until that day comes, we’ll relish in the beautiful images returning to Earth from our one and only remote X-Ray observatory. For the moment, astronomers, especially those who have seen the wax and now potential wane of their beloved telescope, have created petitions to lobby against this, weathering the budgetary constraints of NASA to ensure the telescope endures.

At least, until the next one comes out. Hurry up, Athena!!

If you’re in the US, learn what you can do to save Chandra through this website: https://www.savechandra.org. Lobby your nearest congressman NOW!

Like what you see? Feel free to subscribe to our blog to receive updates whenever we post.