This is a direct port from my old blog, check it out on the front page!

We’re going back to Jupiter! JUICE, or the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, has launched this Friday and is now headed towards Jupiter. There, it’ll collect and survey the three icy and large moons for show - Ganymede, Callisto and Europa, each with its own subsurface ocean to explore. This’ll probably be done through scanning the surfaces for the building blocks of life, and while we won’t be able to directly map signatures of life, it’ll hopefully provide us a precedent to launch future missions to these icy worlds.

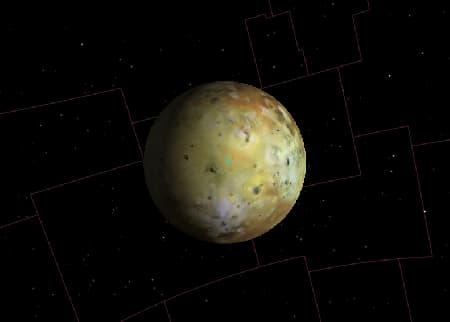

Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem like JUICE is going to check out Io, the first in my bucket list for our Solar System’s top three moons to visit. To me, Io’s an incredibly intriguing world - despite its distance from the sun, it’s a volcano-puckered wasteland, a caustic-green hue covering its’ crust, red and yellow highlights haphazardly put together like an amateur using hair dye. It’s even the most volcanically-active body in the solar system, triumphing the likes of Venus! Even then, it only has a really, really thin atmosphere, so the bluish tinges you see on the planet’s surface is actually sulfur dioxide frost, which has sublimated on the planet’s chilly -178 degree surface (if not for the volcanoes!)

I also wanted to hone in on the reasons why Io is a charred rock compared to its icy siblings, and that can be traced to one thing only - tidal forces. See, Io orbits closest to Jupiter - around 420,000 kilometers away, slightly further than the moon to our Earth. However, Jupiter’s gravitational field strength is almost 2.5 times stronger than ours - which can lead to some interesting tidal effects. First, Io’s tidally locked - one side always faces Jupiter while another stares off into outer space. Next, Io experiences intense tides - similar to the moon tugging on our oceans, but if our tides were solid rock and incredibly intense - Io’s rock tides fluctuate by about 100 meters periodically, making the planet’s surface appear to be ‘breathing’ due to the up and down motion of its surface.

Io’s tidal heating is strong enough to induce volcanism on its surface, where almost 400 active volcanoes are dotted around the crust. Albeit a similar phenomenon of tidal heating presides over Earth, helping to keep the core warm, Io’s tidal heating actually arises from a more turbulent friction between its Jovian overlord and the other three large moons in the system, which pull on the moon from both sides. The strength of this “pulling” varies with Io’s orbital positions, which leads to a constant deformation of the moon’s interior, generating heat. It’s thought that Io could have once been an icy world - it may have been captured by a young, hot Jupiter which would have vaporized Io’s ice and subjected it to the tidal effects we see now.

Moving on from the gravitational effects, Io, with its molten iron core, cuts through the region where Jupiter’s magnetic field is strongest, functioning as a kind of electrical generator. Charged particles generated by Io then flow poleward, creating auroras at Jupiter’s poles. Even then, Io’s still blasted by radiation traveling through Jupiter’s field lines, making creating a probe resistant enough to electromagnetic interference not only difficult but expensive. As the icy Jovian moons orbit further away, this effect is less profound and the electronic instruments aboard JUICE won’t be as perturbed.

For a long time, Io was believed to be a dead rock. It’s interesting seeing interest in Io resurgent despite the near-celebrity status of its cousin Europa. Perhaps JUICE has paved the way for interest in the Jovian system to flourish as it did when Voyager 1 visited - whatever it is, I’m glad more and more people are willing to share their experiences exploring this exotic, often overlooked celestial body.

Like what you see? Feel free to subscribe to our blog to receive updates whenever we post.