Sorry for the long hiatus, but I’m back! Had a couple things to sort through first - more ‘articles’ coming your way soon! This is intended to be a story about the moon and how it’s evolved, and I’m hoping to get back into writing more in the future.

I have actually been writing a bit. If it goes well, I’ll be uploading some snippets of my creative writing here soon, alongside with these ‘astro-articles’. Thanks for being patient, and I hope you enjoy! - J

Our moon. Known for its craters, mares, and insidious ‘dark side’, it has captivated ancient philosophers and modern photographers. It is an integral part in dozens of religions, and has proven interesting enough to hook astrogeologists to their office chairs, each racing to be the first to decipher how the moon’s surface evolved over the ages.

Though the moon’s surface doesn’t change much now, our moon once sported the fire-spewing, unpredictable volcanoes of Earth in its past. This discovery, although obvious in hindsight, was a recent one, as it was only in the 1600s did Galileo find craters, large ridges, valleys on the moon when he used his telescope to perform a survey of the natural satellite. Ridges and valleys on a body as small as the moon imply a strong force sweeping through an area caused by things outside of water.

It’s easy to see how our ancestors couldn’t have fathomed the existence of the extreme features we see on our moon. The Earth’s atmosphere ensures that any craters or ridges that appear on its surface will gradually erode until it becomes one with its surroundings again. So it was, for the 5,000 years of civilisation before Galileo, that the moon was simply accepted for what it was.

Though Galileo’s discoveries of the moon were deemed heretical by the Church, the moon did see active volcanism up to 120 million years ago. It must’ve been a spectacle for those dinosaurs, seeing the red-orange glow of a volcanic eruption happen on a celestial body unlike theirs. This, however, poses the questions: why did the volcanoes stop, and what could’ve caused them in the first place.

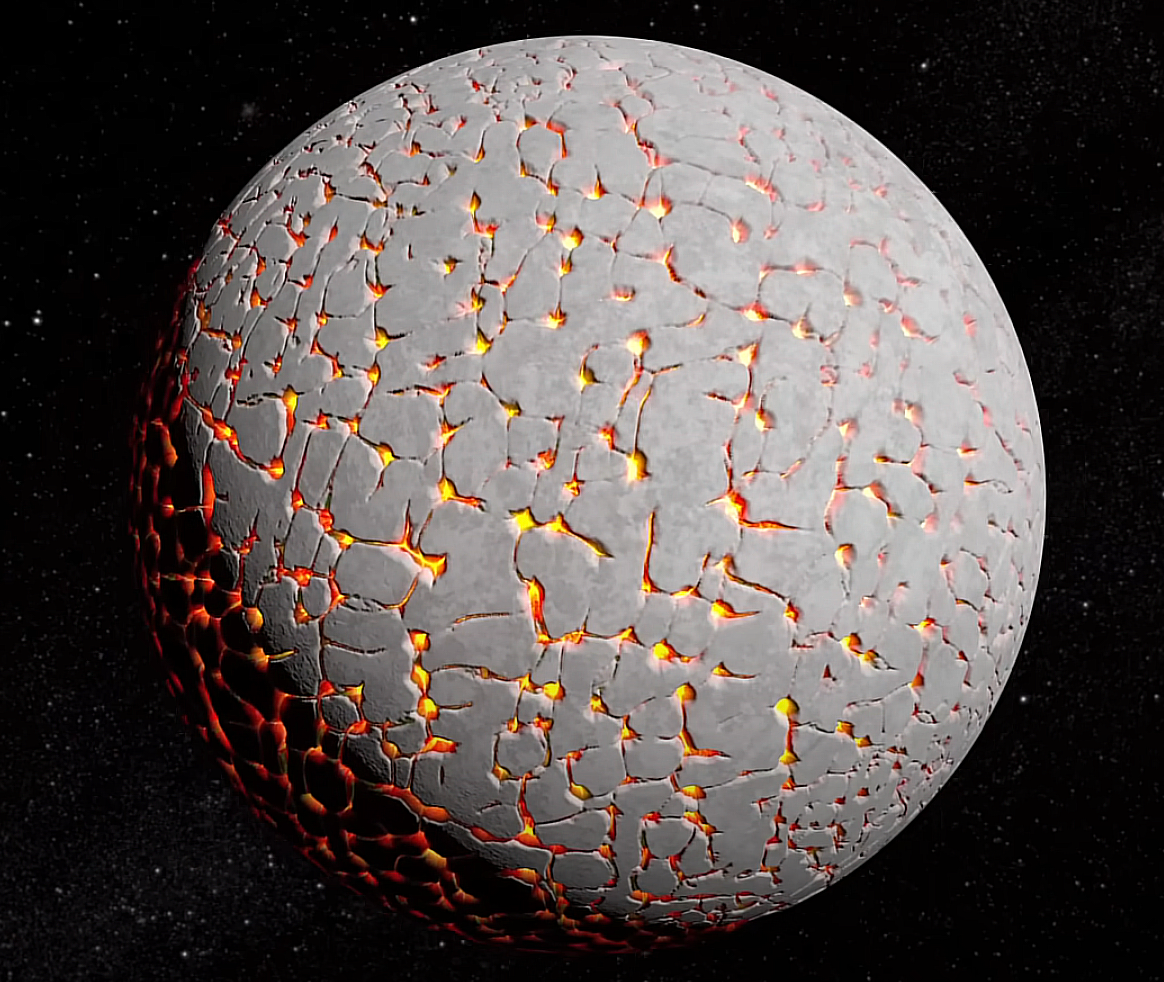

Much like on Earth, lunar volcanoes would’ve erupted when the pressure from the molten rock (magma) under the crust leads to this molten rock forcing its way onto the surface. To create this magma, the moon must’ve been sufficiently hot in its past, and this heat must’ve dissipated as time went on. Still, how hot must the moon’s core have been if it were to cool beyond the point of tectonic activity?

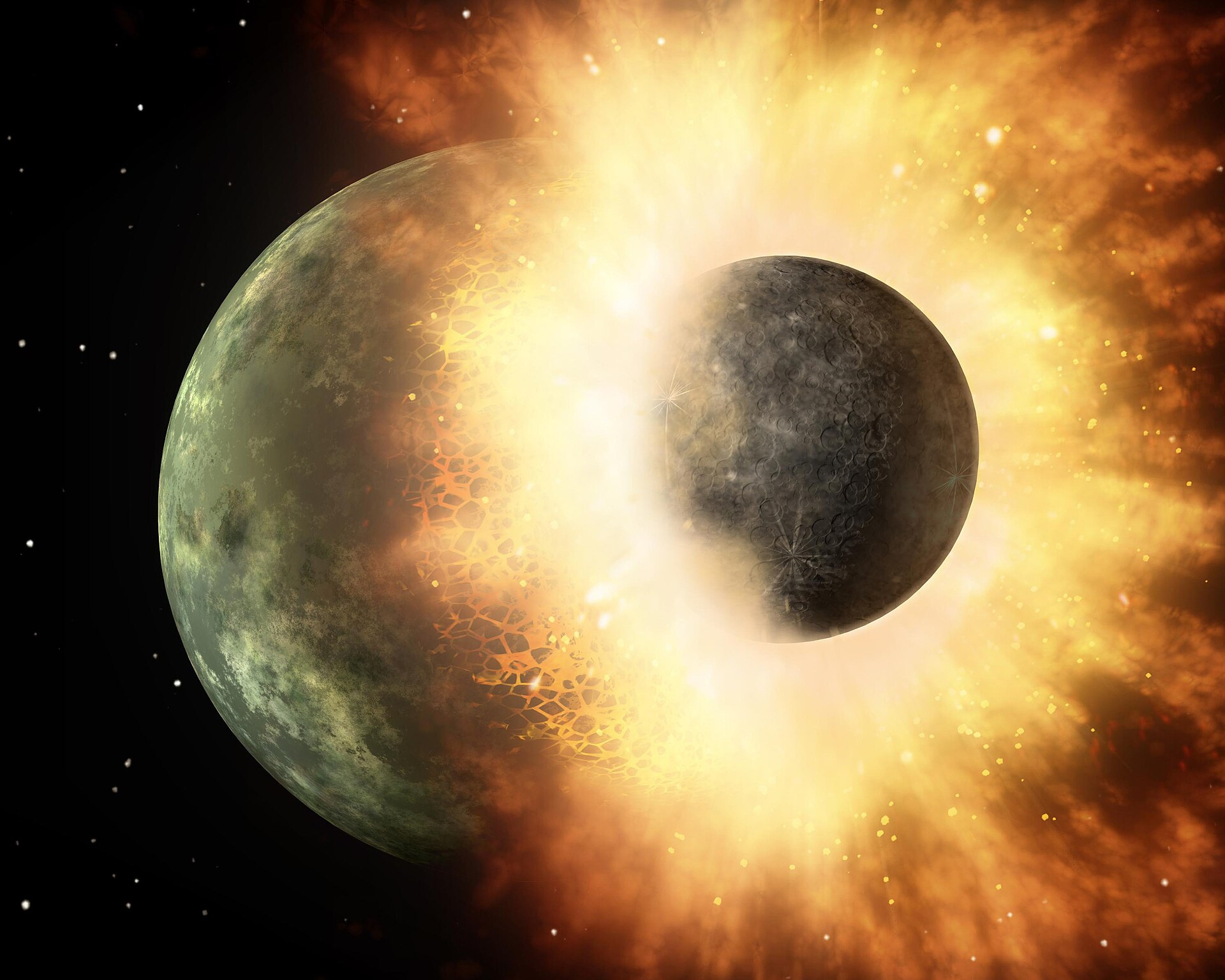

The answer lies in how the moon formed. Although the precise way it did so is still contested, it most likely did so from the torrid ring of debris left over from Earth’s collision with Theia, a mars-sized planetoid from the early solar system. Its core was red-hot, having just been agglomerated. As a result, eruptions, much the same on the young Earth’s Hadean period, dominated the lunar surface during this period.

Volcanoes could explain some of the features we see on the moon’s surface. Although there’s been several theories to the creation of the dark patches, or Mares, some of the most pervasive ones involve several asteroid impacts, differences in cooling rates and - you guessed it - volcanoes. Rock that cools quickly is typically darker than rock which doesn’t, which could explain the irregularities in the surface. With the rampant volcanism of any young pseudoplanetary body, lava would cover a large portion of the surface, which would then cool faster than when the moon first formed, creating darker rocks. An inadvertent consequence of the volcanic theory is that the lava coating the moon’s surface would’ve been extremely rich in minerals. Even today, with long-enough exposure time, the different colours reflected by the lunar minerals deposited by these volcanic eruptions can be seen, dazzling in splotches of blue, red, and yellow alike.

With the Late Heavy Bombardment reaching its apex some 600 million years later, the moon’s core was able to maintain its heat from the impacts of meteorites. Each asteroid impact created a crater on its surface, whilst the larger meteorites would vaporise the rock around its impact, turning it into lava. This lava would then solidify, creating another pathywayfor the creation of the mares. In reality, the truth of the moon’s formation is almost certainly a mixture of all three methods, though we can never know for sure until we get up there.

After this, the solar system remained relatively stable, until finally the moon’s core As the moon’s mantle solidified, the volcanoes went dormant, until the moon’s final eruption some 100 million years before humanity took its first steps. This leads us today, where humanity finds itself at the perfect time to explore a barren, lifeless moon.

Still, the moon’s surface is harsh, completely coated in a sheen of easily-disturbed dust born from the cosmic radiation that slowly ground down the volcanic rock. It threatens to grind down any heavy machinery we bring over, and is another barrier to moon exploration that we need to consider.

Studying the evolution of the surface of the moon might yield insights into its formation. With new data, we can refine our models for the formation of large satellites around planetary bodies - and the effects it might have on its parent right after formation. Since the effect this satellite has on the planet is not negligible, discovering how the evolution of our moon might’ve paralleled our own Earth is important for determining the true conditions for sapient life.

Honing our species’ skill with astrogeology can prove to be a valuable asset in the future, when off-planet colonies can be established. Making the Earth we stand on more predictable by surveying it and its parities with the moon’s surface is extremely important and can reduce the number of accidents we have when setting up colonies elsewhere. In addition, it can help us find economically viable locations to set up colonies, giving us the tools to make a sustainable, integrated colony system to benefit humanity in the near future.

Like what you see? Feel free to subscribe to our blog to receive updates whenever we post.

READ MORE!