Astrophotography wouldn’t be anything without optics. To peer past the 6th-magnitude requires ‘eyes’ much stronger than our own - specifically, we need tools that help us gather more light, magnifying them for our own use. In other words, we’d need something that’d help us catch more light - a telescope. We’ve been able to pry valuable data from them, providing a source for a steady stream of surprises.

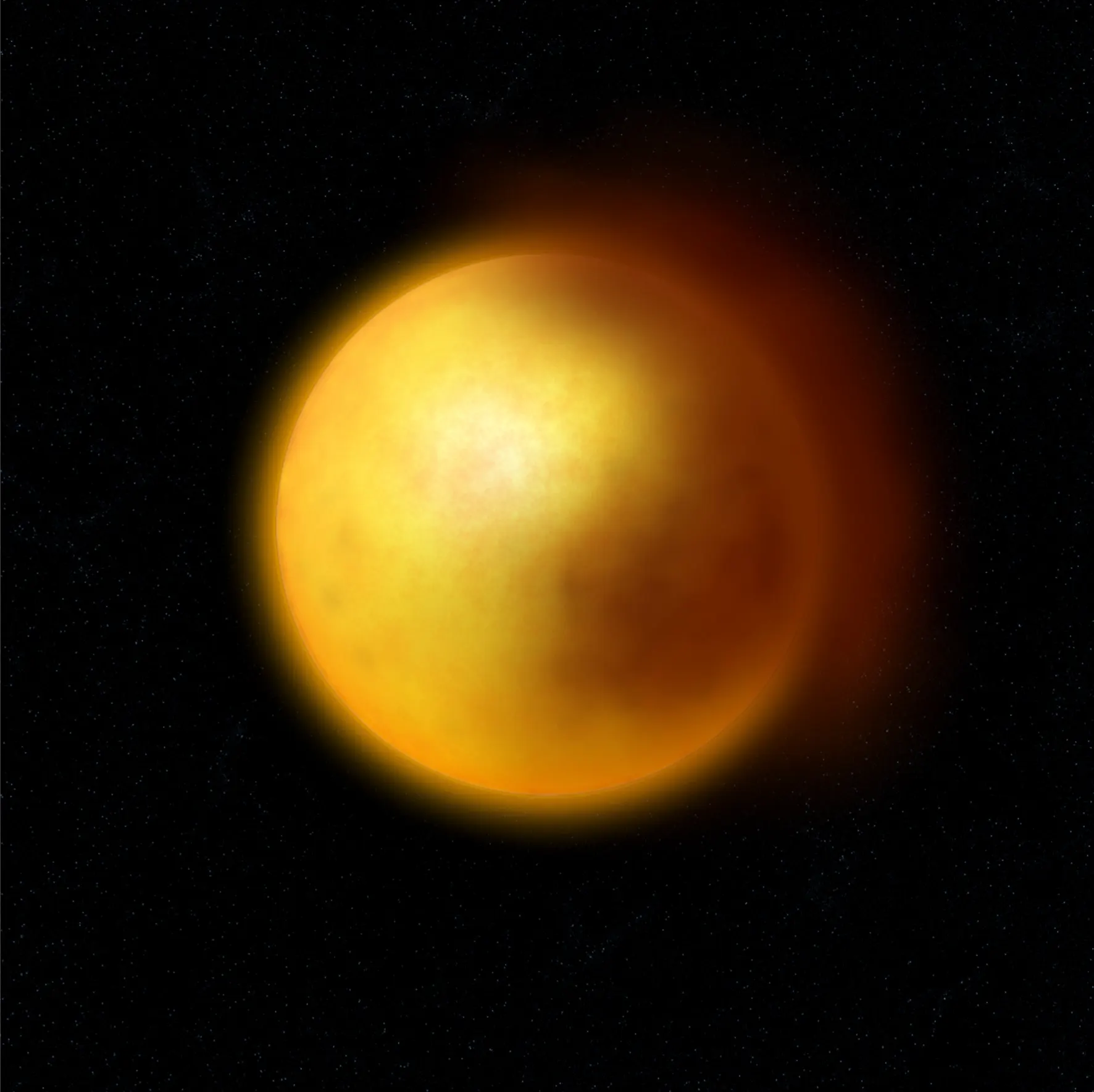

Located right in the heart of Corona Borealis, R Coronae Borealis (RcB), by all standards, is a ‘surprise’. A G-type hypergiant, it shines at a brightness of 10,000 suns, shining at a temperature of 6,750 kelvins. Located around 1400 parsecs away, it’s a 6th magnitude star - just barely above the threshold for it to be visible.

You’d expect the mass of the progenitor star to be pretty large, given that it spans a diameter 85 times that of our sun. Now, here’s the curious part - instead of being some O-type star at some point, RcB’s actually got a mass lower than that of our sun. Huh?!? Even worse, it’s a variable star - it seems to dim unpredictably, going from a 6th magnitude, naked-eye star to the 15th magnitude, a 4000-fold decrease in the visual brightness of the star!

Since the discovery of RcB’s variability in 1795, another 150 of these stars have been discovered scattered around our galaxy. Each of them seem to pulsate irregularly and have no discernable hydrogen spectral lines in their spectra. It’s theorised that these ‘pulsations’ are actually ejections of carbon and ‘metallic’ dust that condense once it’s clear of the star’s hot corona, forming clouds that block light from the star.

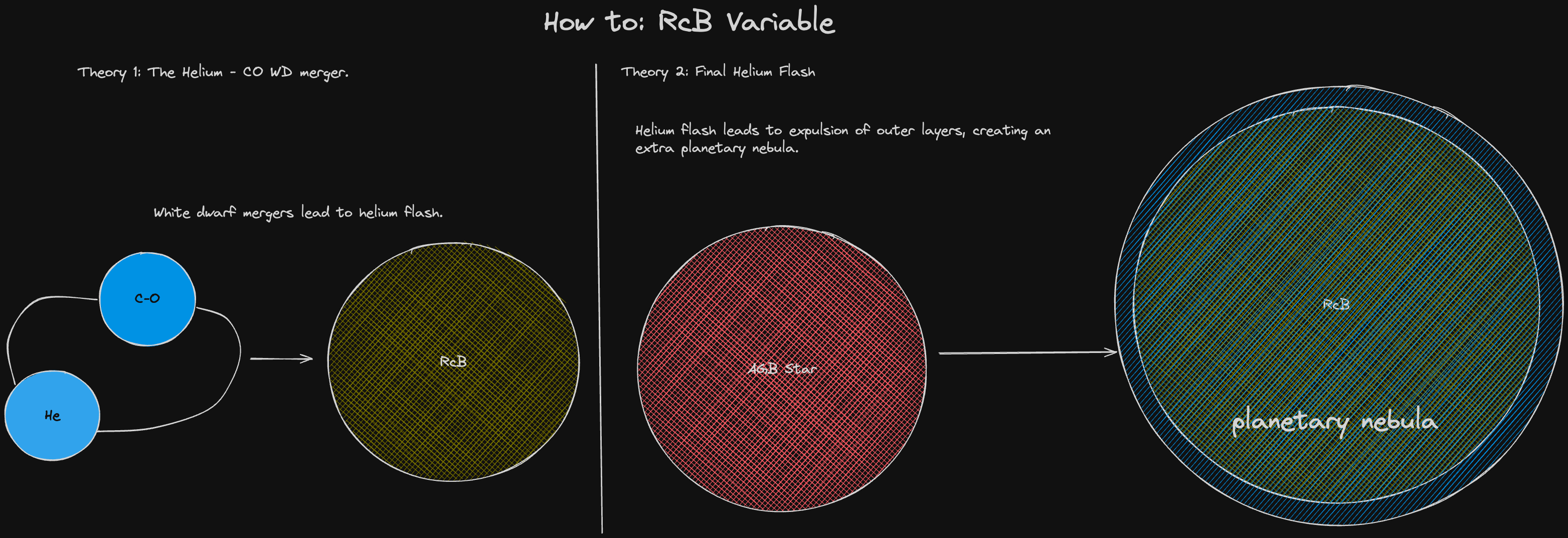

This mystery’s puzzled scientists for nearly 200 years. With the advent of new telescopes and breakthroughs in our understanding of white dwarves and post-AGB evolution (link this), we’ve gained tremendous insight into how these stars could’ve formed. As of now, we’ve narrowed this down to two methods:

- The White Dwarf Merger. These stars, being hydrogen-deficient, mostly consist of helium and various ‘metals’ such as carbon and oxygen, pointing to a special merger between a helium and carbon-oxygen white dwarf.

- The Post-AGB flare. During the last stages of a star’s life, the star’s kept from collapsing through shell-burning, where material is fused in shells around a really, really dense core. Sometimes, as the star loses much of it’s outer envelope, it’s possible for the helium-fusing shell to reignite, causing the star to expand again!

A schematic diagram for both methods of RcB Variable formation! Credit: Original Content.Evidence has surfaced that the latter is the most likely cause for the creation of this star. For example, Sakurai’s Object, a similar star, was a planetary nebula central star before expanding into an RcB variable. As helium white dwarves require very specific conditions to form, it’s safe to say that many of the RcB variables that we see are probably post-AGB stars.

It’s projected that this honeymoon phase won’t last for long - unfortunately, it heralds the last gasp of a dying star. At any moment, R Coronae Borealis will cease helium fusion once again, regressing back into a white dwarf. It’s as if these stars have been given a second wind - only to have it be stripped of them by the inexorable passage of time.

That’s one ‘surprise’ down. Another couple ten thousand or so unanswered questions to go!

Like what you see? Feel free to subscribe to our blog to receive updates whenever we post.