This is an experiment with longer articles. Sorry for the wait - needed to consider some personal things.

Past the rocky planets of the solar system lie the ice giants, too big and gassy to be considered rocky planets, too small and lacking the hydrogen to be considered conventional gas giants. One of these planets has the unfortunate distinction of being called Uranus - and it might as well be, having not been studied in great detail since the Voyager 2 missions.

So, today, we’ll be taking a deeper dive into the moon system of Uranus, often overshadowed by its neighbours Saturn and Neptune. From the cliffs of Miranda to the icy veneer of Oberon, don your Spacer’s helmet, hop into your spaceship, and plot a course to this light blue planet!

The Inner and Outer Moons

It’s theorised that the Uranian inner and major moons formed from the Uranian circumplanetary disc, created from the remaining material from Uranus’ formation and material from another devastating collision earlier on in the planet’s life. This collision not only contributed to the formation of the inner and major moons but also left the planet with its trademark 97 degree tilt.

So, as your spaceship approaches the blue planet, automated probes are sent out to do The inner moons, all of which are not small enough to round themselves out (through a process known as hydrostatic equilibrium), are theorised to collide with each other constantly, being in such close proximity to one another. As a result, their overlap with the wider Uranian ring system is most likely causational; when moons collide, debris is ejected, leading to the creation of rings as this debris disperses. Being so close to one another, these moons are likely to collide and debris to scatter, replenishing the Uranian rings. The largest one of these moons is called Puck and has a diameter of 162 kilometres.

Now, we move on to the irregular moons of Uranus. These moons are relatively small (with comparable sizes to the inner Uranian moons). What separates them from the remainder of the Uranian system is that they do not orbit on the orbital ecliptic plane - so they don’t orbit on the same ‘disc’ as the other moons. Some of these moons, in fact, actually rotate the opposite way to Uranus (known as a retrograde orbit).

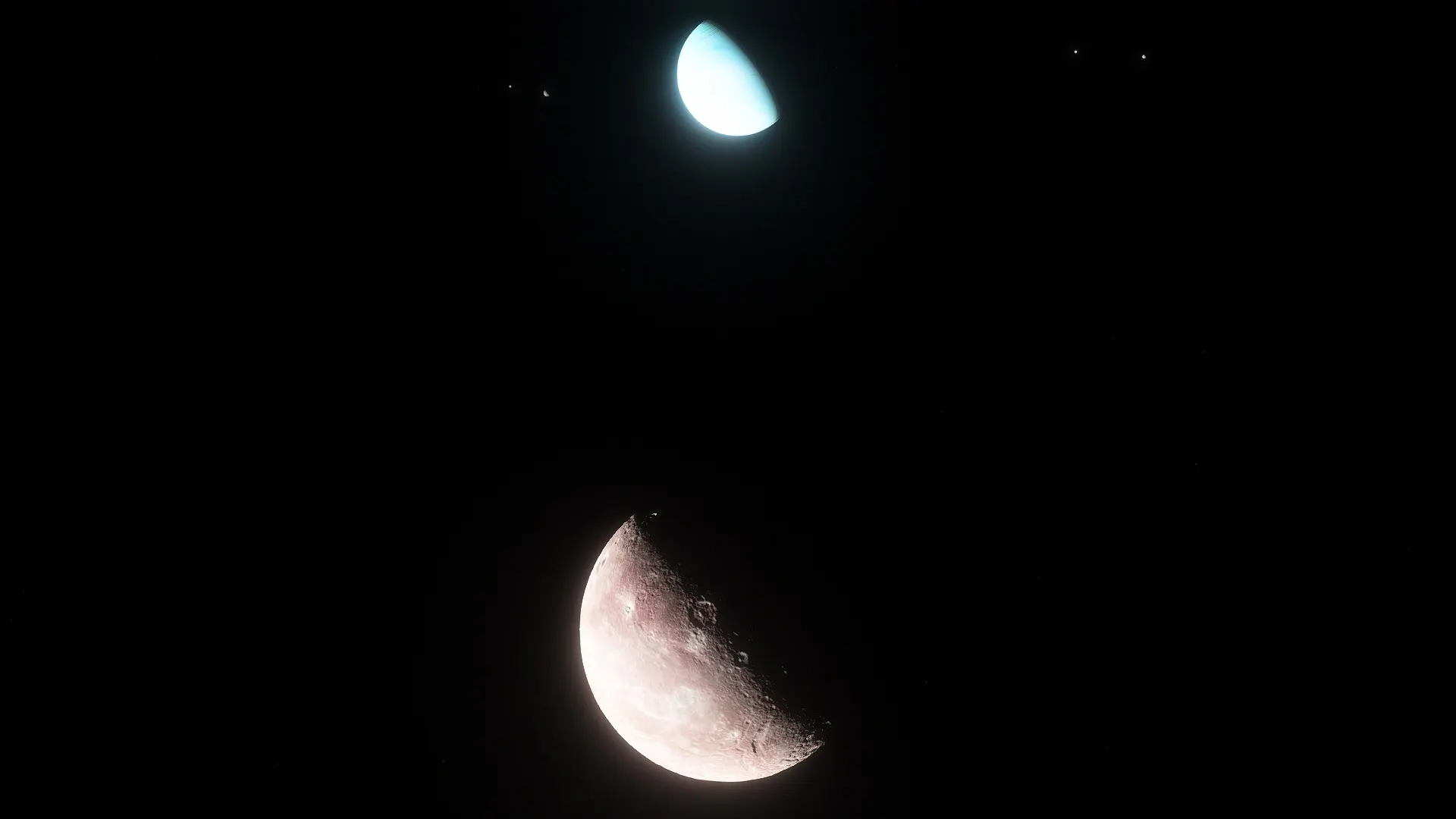

Its been theorised that these moons were Centaurs in the past that were captured by Uranus. It would explain why these planets have extremely eccentric orbits, as well as why all of them are so small. They’re curiosities, these ones, and they orbit so far away from Uranus that the planet looks only like a tiny crescent from afar!

An Article within an Article - the Major Moons

Saving best for last, your spaceship realigns itself to begin a tour of Uranus’ biggest moons. Having 5 major moons, although still small, this far-flung, overshadowed methane clump’s lunar system might still have something of scientific worth for all of humanity to use. It seems as if the moons have aligned themselves perfectly for your spaceship, so it’s only fitting that this tour be done.

After having toured the Caliban group, the first moon you arrive at is Oberon. Named after the fairy king from Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, it’s far enough away from the planet that it orbits outside its magnetosphere. Though its surface does, as a result, bear the brunt of the solar wind, radiation is not being sent directly to the moon’s surface by magnetic fields, meaning that its surface is considerably lighter than the other Uranian moons. In fact, the moons in the Uranian system have some of the lowest albedos - surface reflectivity - in the entire solar system! This might be a great location for a moon base once battery supply chains are better established, you think to yourself.

Leaving Oberon almost as quickly as you arrive, Titania soon appears as a grey-black dot, growing larger and larger as your automated science instruments roar to life. Named after the Queen of the Fairies in “A Midsummer’s Night Dream”, its orbital period of 8.706 days, it’s tidally locked, always facing the blue ice giant it calls its planet. With a density of 1.71 g cm$^3$, its interior, like most objects at comparable distances in the solar system, is likely to be a mix of ice and rock.

In addition, it’s one of the more reflective of Uranus’ moons, with icy-white patches of frost hinting at the existence of cryovolcanoes, albeit not at the scale of Enceladus or Europa. These “volcanoes”, which are actually more like geysers that shoot hot water from a subsurface ocean closer to the core, therefore point to there being another subsurface ocean below Titania, with the possibility of having life. Despite having only a twentieth of the mass of our moon, the tidal forces of Uranus are likely to be enough to lead to tidal heating - so during different parts of Titania’s orbit, it stretches internally, leading to friction and producing heat that keeps its core warm.

Umbriel soon appears on your viewport, its deep grey surface reflecting only 10% of incident light back to you. It’s another geologically inactive moon, and its surface reflects that. Unlike Titania, which has a ‘young’ surface (pointing further to cryovolcanic activity), Umbriel has an old, cratered surface, with only Oberon having more craters than it.

Then comes bright Ariel. With the highest reflectivity of any of the Uranian moons, not much actually distinguishes it with the rest of the system. The ‘darkening’ of the moons in the Uranian systems are likely due to ‘contamination’ by organic molecules; compounds like tholins typically contribute to the dark streaks on other moons, though they seem to be more evenly distributed among the moons in the Uranian system.

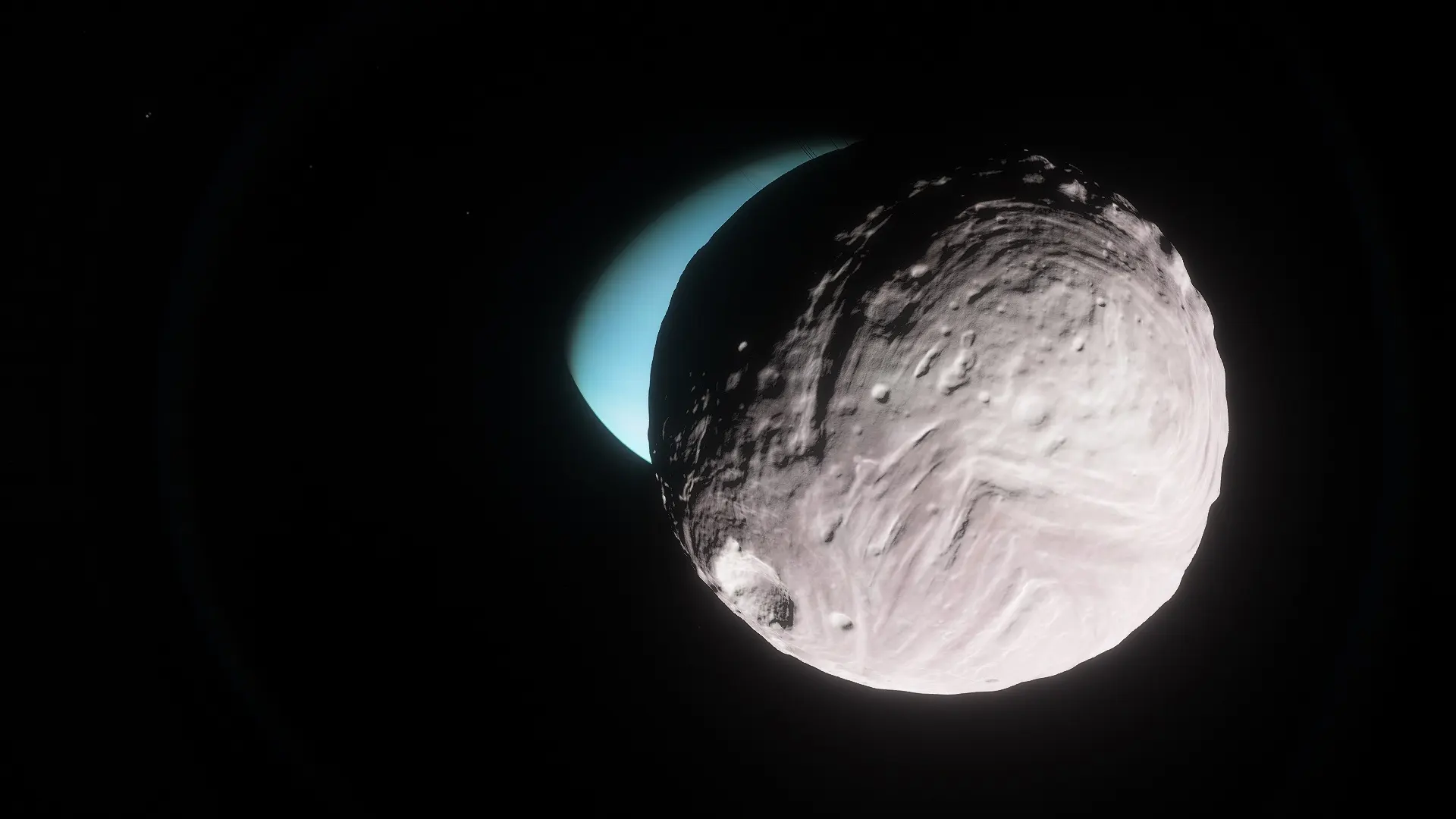

Finally, Miranda appears on your screen! The smallest of the Uranian major moons, it’s just teetering on the edge of being a sphere (any smaller and it’ll look like Vesta. In fact, despite its size, its got the tallest cliffs of any body in the solar system, with Verona Rupes taking the crown at almost 20 kilometres tall.

The Uranian lunar system might be the lightest in the solar system, but like any other planet, it’s got its own quirks. Perhaps, some time in the far future, our tall descendants will be descending down Verona Rupes in their radiation suits or exploring the subterranean Titanian ocean, wondering what their ancestors didn’t see in the planet.

Fear not! An exploration of the Uranian system may happen soon. There’s actually a proposal to send probes to Uranus to better study its lunar system, since it only got a brief Voyager 2 flyby. Though this mission won’t likely take place until 50, 60 years after writing this article, I’m already excited for what might follow!

All photos taken in SpaceEngine.

Like what you see? Feel free to subscribe to our blog to receive updates whenever we post.